This Is for Vel: Recognizing and Confronting Animal Hoarding

- behavioreducationl

- Jul 13, 2025

- 4 min read

By Cait Mistral & Lori Torrini

Originally written by Cait Mistral and adapted with permission for publication by Lori Torrini

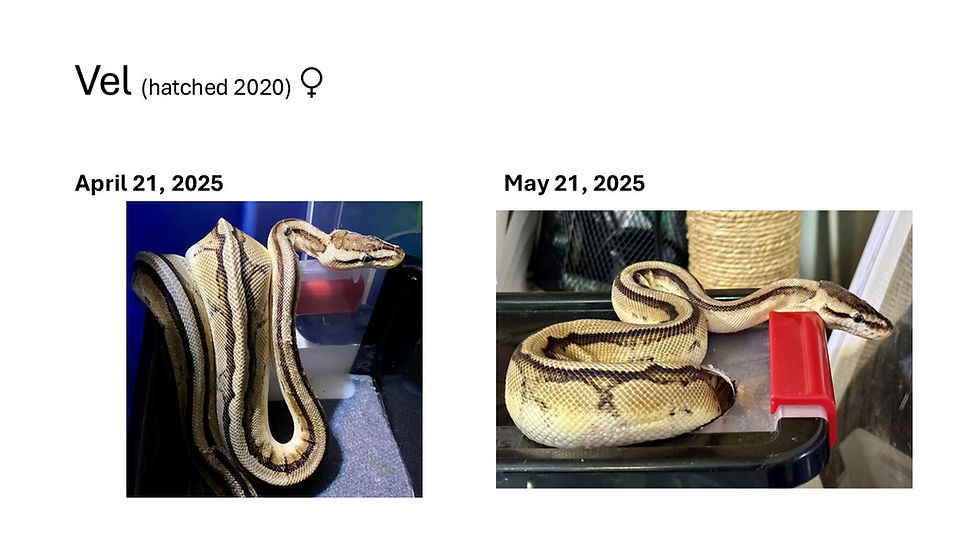

The recent rescue of 67 snakes from a case of criminal neglect has drawn attention to an often-hidden crisis: animal hoarding. While updates on the rehabilitation of these snakes will continue for months, we must also confront the deeper issues, particularly how people who claim to love animals can allow such suffering.

This post is for Vel, one of those snakes, and for all others who’ve endured the same.

Understanding Animal Hoarding Disorder (AHD)

Animal Hoarding Disorder (AHD), also known as Noah’s Syndrome, is a psychiatric condition and a subset of Hoarding Disorder, now recognized in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is characterized by compulsive accumulation of animals, failure to provide minimal care, and lack of insight into the harm being caused to both animals and humans (Nadal et al., 2022; Wilkinson et al., 2022).

Unlike temporary hardships where overwhelmed keepers seek help, AHD involves denial, delusional thinking, and persistent acquisition despite deteriorating conditions (Stumpf et al., 2023; Nadal et al., 2022).

Profile of an Animal Hoarder

Hoarders are often middle-aged women living alone, though cases span gender, age, and socioeconomic background (Nadal et al., 2022; Sacchettino et al., 2023). Many present as animal lovers or rescuers. But in reality, their need to possess animals eclipses the animals' actual needs.

Common features include:

Poor sanitation and structural decay.

Severe neglect of animals (malnutrition, untreated disease, behavioral trauma).

Lack of insight or refusal to acknowledge harm.

Rejection or misuse of help offered by others.

These conditions were seen in the case of the 67 rescued snakes: skeletal thinness, dehydration, parasitic infestations, and behaviors indicative of extreme psychological distress such as startle responses, hiding, fleeing, and complete disengagement from human presence.

What the Science Shows

Recent research paints a grim picture:

The average number of animals hoarded is 44–64 per case (Nadal et al., 2022; Wilkinson et al., 2022).

In up to 60% of cases, dead animals are found onsite (Stumpf et al., 2023; Wilkinson et al., 2022).

Recidivism rates range from 25% to over 60%, even after legal intervention (Nadal et al., 2022; Wilkinson et al., 2022).

Most hoarders acquire animals through unregulated breeding, donations, or informal adoptions (Stumpf et al., 2023).

These animals are not just physically ill, they suffer psychologically from years of isolation, stress, and deprivation (Sacchettino et al., 2023). Many cannot recover fully, and euthanasia becomes necessary in severe cases due to behavioral deterioration or dangerous behavioral issues rooted in trauma (Stumpf et al., 2023).

Differentiating Overwhelm from Hoarding

It's crucial to distinguish hoarding from genuine hardship. Anyone can find themselves unable to care for animals due to life events. The difference lies in response. Responsible keepers ask for help. Hoarders deflect, deny, or rationalize the harm.

As Patronek and Nathanson (2009) outlined, hoarders typically fall into categories:

Overwhelmed people who initially provide care but become unable to maintain it.

Rescuers who compulsively save animals beyond their capacity.

Exploiters or breeders who use animals for status, profit, or control without empathy.

In all forms, hoarders prioritize their compulsion over animal welfare/wellbeing.

Recognizing the Signs

Key warning signs of animal hoarding include:

Unusually high number of animals.

Underfed or dehydrated animals, often with untreated medical conditions.

Dirty enclosures or cages with feces, shed skin, or soiled bedding.

Maladaptive animal behaviors.

Strong odors, unsanitary household conditions.

Defensive or hostile responses from the human when other raise concerns.

Continued acquisition of animals despite acknowledged hardship.

These signs were present in the recent snake rescue and mirror global data across species (Wilkinson et al., 2022; Sacchettino et al., 2023).

What You Can Do

Report suspected hoarding. If you see something, say something. Animal control or local law enforcement must be notified.

Support real rescues. Donate to legitimate, accountable sanctuaries and shelters like Spirit Keeper Animal Sanctuary where transparency, veterinary oversight, and behavioral rehabilitation are priorities.

Don’t enable. Offers to help hoarders personally often end in manipulation. Unless there's a clear, monitored intervention plan, walk away and report instead.

Talk openly. Within the reptile and exotic animal community, we must question the normalization of over-accumulation. Jokes about animals being “addictive” or “potato chips” can mask real issues.

A Final Word

Not every reptile keeper who has many animals is a hoarder. But some come perilously close. Take inventory of your own practices. Are your animals enriched, healthy, and emotionally regulated? Are you thriving, or just coping?

This is a moment for reflection, for Vel, and for all the animals still waiting.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Nadal, Z., Ferrari, M., Lora, J., Revollo, A., Nicolas, F., Astegiano, S., & Díaz Videla, M. (2022). Noah’s Syndrome: Systematic review of animal hoarding disorder. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, 10(1), 1–21.

Sacchettino, L., Gatta, C., Giuliano, V. O., Bellini, F., Liverini, A., Ciani, F., Avallone, L., d’Angelo, D., & Napolitano, F. (2023). Description of twenty-nine animal hoarding cases in Italy: The impact on animal welfare. Animals, 13(2968). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13182968

Stumpf, B. P., Calácio, B., Branco, B. C., Wilnes, B., Soier, G., Soares, L., ... & Barbosa, I. G. (2023). Animal hoarding: A systematic review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 45(4), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.47626/1516-4446-2022-3003

Wilkinson, J., Schoultz, M., King, H. M., Neave, N., & Bailey, C. (2022). Animal hoarding cases in England: Implications for public health services. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 899378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.899378

Comments